We make these calculations automatically, but we demonstrate an intuitive knack for economics and game theory when we react to the difference in value between 2.6 blocks, points, threes or rebounds. Scarcity is a focus of both these overlapping mathematical fields.

Although fantasy basketball owners have a fantastic intuitive of grasp categorical scarcity, positional scarcity is more subtle. That subtlety lends itself to a maladjusted trade market, which means there is a lot of opportunity for savvy managers. Since most fantasy trade deadlines are about a month away, the time to strike is now.

This week, we dive into positional scarcity, and try to find ways to use it in the fantasy marketplace.

Positions are unevenly distributed amongst tiers

There are similar numbers of point guards, shooting guards, etc., in the NBA. This is why the intuitive understanding of "there are tons of points and very few blocks" won't help us. Every team has roughly one starter and two bench players per position per team.

But most fantasy leagues only deal with the top-200 or so

We make these calculations automatically, but we demonstrate an intuitive knack for economics and game theory when we react to the difference in value between 2.6 blocks, points, threes or rebounds. Scarcity is a focus of both these overlapping mathematical fields.

Although fantasy basketball owners have a fantastic intuitive of grasp categorical scarcity, positional scarcity is more subtle. That subtlety lends itself to a maladjusted trade market, which means there is a lot of opportunity for savvy managers. Since most fantasy trade deadlines are about a month away, the time to strike is now.

This week, we dive into positional scarcity, and try to find ways to use it in the fantasy marketplace.

Positions are unevenly distributed amongst tiers

There are similar numbers of point guards, shooting guards, etc., in the NBA. This is why the intuitive understanding of "there are tons of points and very few blocks" won't help us. Every team has roughly one starter and two bench players per position per team.

But most fantasy leagues only deal with the top-200 or so fantasy players – and smaller leagues barely go outside the top 150. Inside the fantasy top 200, the distribution of positions is not even. For example, the top 200 includes 65 players eligible at power forward, but only 54 at point guard (this article uses ESPN's position designations, but most other sites are similar enough that the conclusions apply directly).

Furthermore, fantasy teams are top heavy, so we also need to consider the distribution of players who are very good producers. We cannot just consider all rosterable options equally – Kevin Durant should count for more than Al-Farouq Aminu. We need to develop a deeper understanding than just that there are more power forwards worth owning than there are point guards. We want to know what positions are abundant and which are scarce, amongst the elite, the startable and the rosterable.

What is the positional distribution?

This is best answered with some visual aids.

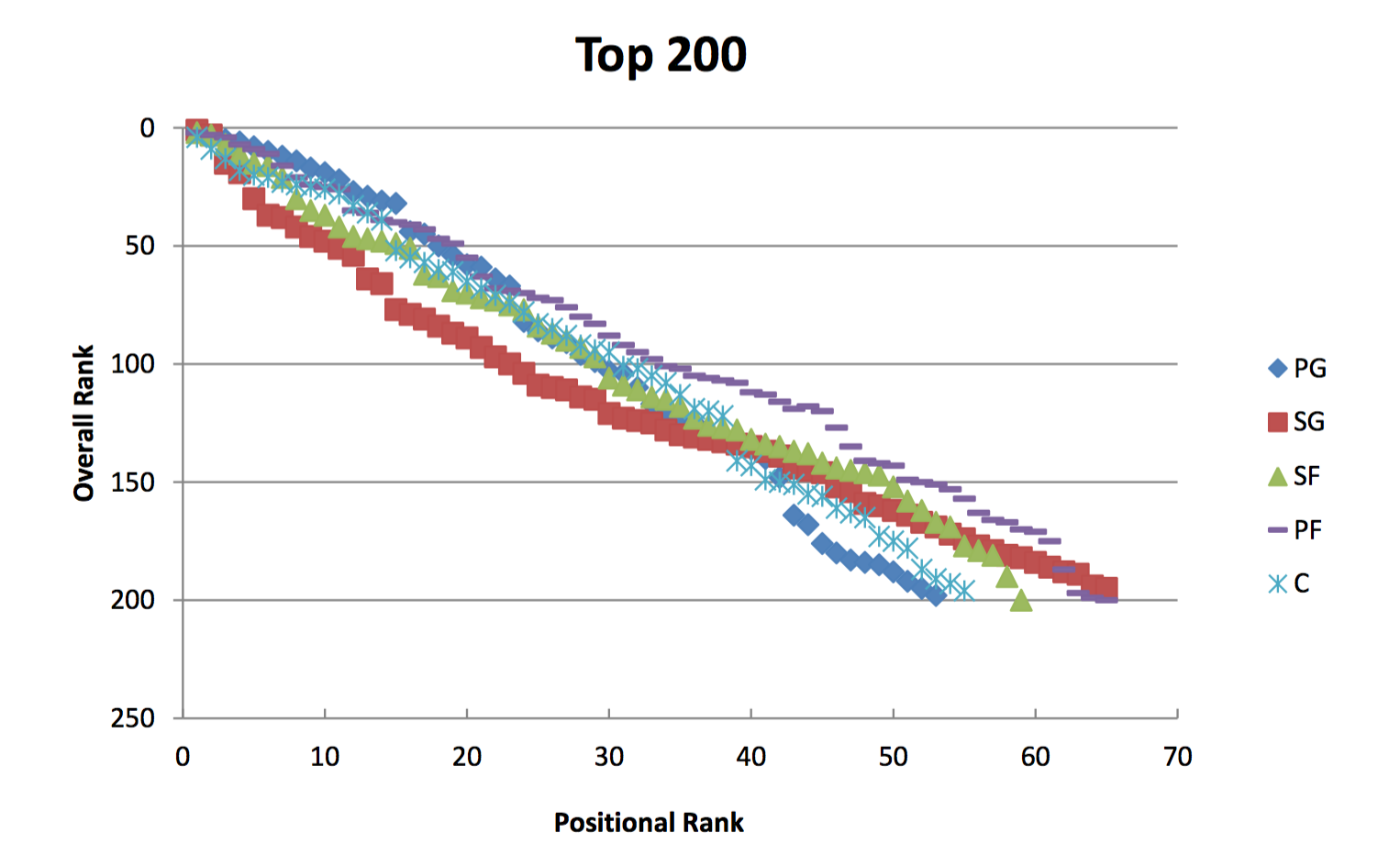

The graph below shows the fantasy top 200. As you move left to right, players become lower ranked at their position. As you move top to bottom, players become lower ranked overall. Each position has a shape and color assigned to it.

This visual gives a general overview of the players in the fantasy universe.

Quick graph explanation: Look straight up from the 20 along the bottom of the graph. We see the red square clearly on the bottom, at roughly the 100 line. This means that the 20th-ranked shooting guard is worse than the 20th-ranked player at any other position (because the red square is on the bottom) and is roughly the 100th-best player in fantasy (because he is on the 100 line). Keep going up from the 20 and we see either the blue diamond or the purple hash on top, hovering over the 50 line. This means the 20th-ranked point guard and power forward are both better than the other positions (because they are on top), and both are roughly the 50th-best fantasy performers (because they are on the 50 line). Finally, follow the 100 line across until it hits the other positions, above the 30 – this shows that the 20th-best point guard produces about the same as the 30th-best player at every other position.

A few trends jump out:

• Very quickly, the shooting guards fall below the rest of the pack. This means that the fifth shooting guard is worse than the fifth player at any other position, and the 30th shooting guard is worse than the 30th player at any other position.

• Shooting guards don't stay on the bottom forever. They meet up with everyone except power forwards at about the top-140 overall spot. In a 10-team league, 130 players are owned, so this is happening at the top of the waiver wire.

• All of the positions except power forwards meet up around the top-140 overall/40th position rank spot.

• Power forwards lead every position between, roughly, position ranks 20 and 60.

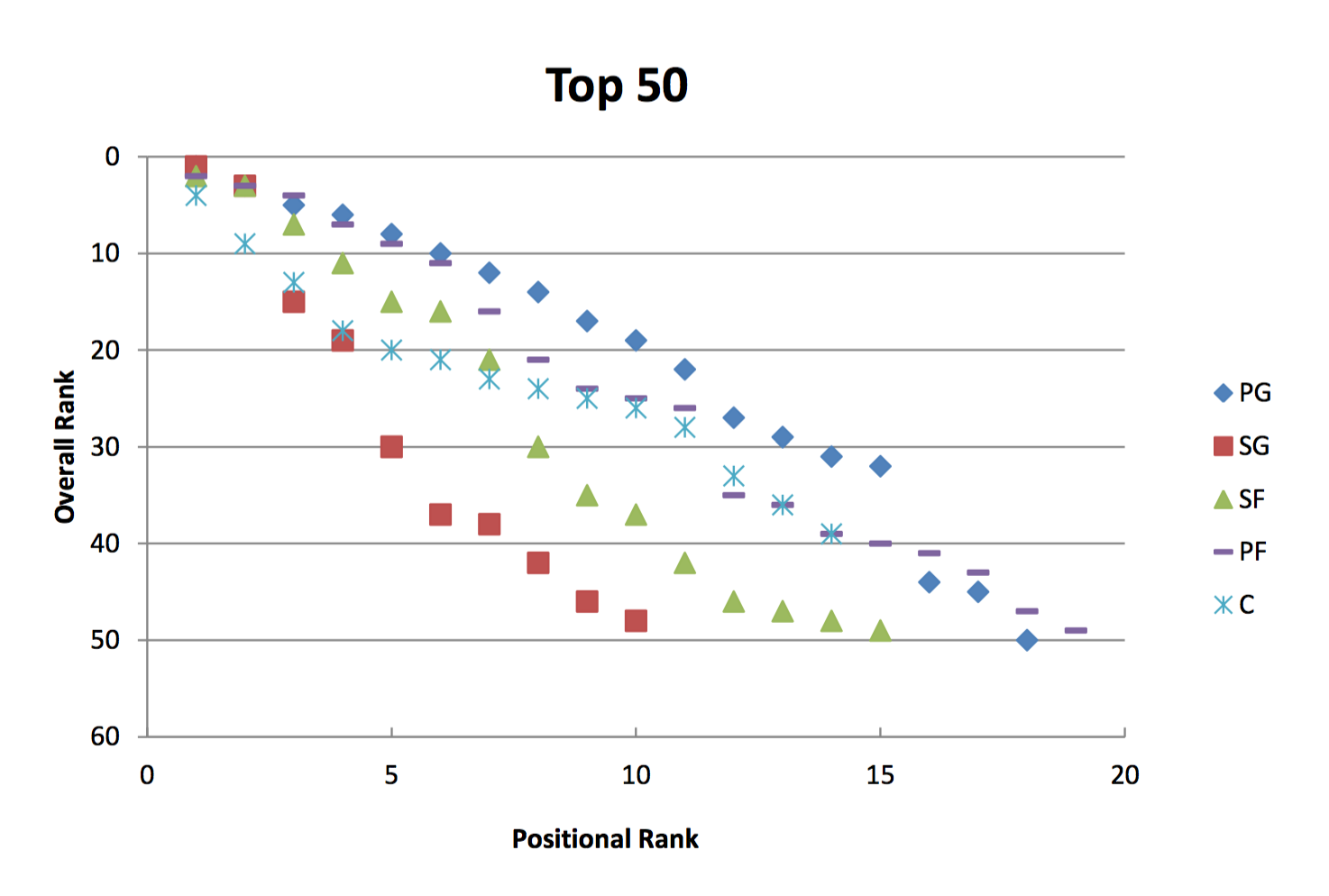

We'll revisit those trends in a minute, but first, let's zoom in on fantasy's real movers and shakers. The following is the exact same graph, except it shows only fantasy's top 50.

By zooming in on the top 50, a few more trends become clear:

• Point guards and power forwards dominate the top 50. There are 18 and 19, respectively, included in the graph. They establish their control inside the top 10.

• A ton of centers are ranked between about 18th and 30th overall, and very few anywhere else.

• After the top 20, small forwards fall clearly below the non-shooting guards.

Finally, I list the same information in two charts. Each chart shows the number of players at each position amongst each tier. For example, there are 23 shooting guards ranked 100 to 150. The charts show the same information as the two graphs above; the first one shows the fantasy universe, i.e., the top 200, while the second focuses in on the top 50.

In the top-200 chart, each row fills a different role in fantasy rosters. The top 50 are your studs, the players who shape your team; 50-100 are the important nightly starters; 100-150 are a lot of players on fantasy benches; and 150-200 are mostly players either on the waiver wire or who might be cut for someone on the waiver wire.

| OVERALL RANK | PG | SG | SF | PF | C |

| Top 50 | 18 | 10 | 15 | 19 | 14 |

| 50-100 | 11 | 12 | 14 | 14 | 15 |

| 100-150 | 13 | 23 | 20 | 19 | 12 |

| 150-200 | 11 | 20 | 10 | 13 | 13 |

| OVERALL RANK | PG | SG | SF | PF | C |

| Top 10 | 6 | 2 | 3 | 5 | 2 |

| 10-30 | 7 | 3 | 5 | 6 | 9 |

| 30-50 | 5 | 5 | 7 | 8 | 3 |

Finally, some trends we see by looking at the charts:

• Point guards completely fall off a cliff outside the top 50.

• The nightly starters tier is evenly balanced.

• Shooting guards dominate the bench and waiver-wire ranks.

• Small forwards and power forwards are abundant amongst the bench ranks, but are much scarcer on the waiver wire.

• Elite shooting guards and centers are scarce.

• Centers are heavily focused in the 10-30 range.

• Point guards have the most even distribution inside the top 50.

Can you hear me now?

The value of an item is based, in part, on what alternatives exist, if any.

I'm from the Boston area, but I worked in the boonies of New Hampshire for a few summers. In Boston, my friends had all sorts of cell plans. A lot had Verizon, but plenty had AT&T (back when it was the only way to own an iPhone), and some even had Sprint. People chose based on what they wanted, be it a fancy new phone, whatever their parents would still pay for, or not wanting to support the annoying Luke Wilson ads. But up in NH, Verizon was the only game in town. I went two summers without meeting a local who used a different carrier.

In Boston, there were options. Verizon was considered the most reliable, but visiting friends still had working phones if they used something else. Up in the quiet hills of rural New Hampshire, however, a phone without Verizon made the same number of phone calls as those weights people wear around their ankles while exercising. Once in a blue moon, an out-of-stater unfortunate enough to have AT&T received a text message. They were unable to reply.

In the case of Boston, there was a competitive market for cell phone plans. Verizon may have been the most reliable, but it didn't offer the fanciest phone, and it wasn't the cheapest option. The phone market in Boston parallels the market for power forwards. Teams can swap elite or sub-elite power forwards to fit each team's strategic preference. A higher-ranked player might not be the best fit for a roster.

The New Hampshire case is that of elite shooting guards. While, technically speaking, there are a lot of shooting guards in the league, there is no true replacement for James Harden or Giannis Antetokounmpo.

But how do I actually use this information?

The fantasy marketplace is so complex and dynamic that there are infinite ways to make use of positional scarcity. What follows is my attempt to highlight the most important.

I'll start with waiver-wire implications, because those are the most universal, and work my way toward trades involving elite players, which the fewest people will be able to take advantage of.

1. Backup shooting guards are dispensable. They are widely available on the waiver wire, which means that most teams have as many as they want or need. Do not cling to a shooting guard outside the top 100 because of the fear that you are dropping someone who might have value in a trade – these shooting guards are so abundant that you are unlikely to find a buyer. The only shooting guards in these tiers who might drive a trade are extreme specialists, such as Thabo Sefolosha in steals.

2. In 10-team leagues, fill the end of your bench with whatever your team needs most, be that a specific position or a category of need. The 40th-ranked player at four of the five positions ranks 132nd to 143rd overall, which is a very tight grouping. That means that there is no value driven by positional scarcity – all of the value is in the players' specific production profiles.

3. To facilitate a trade, offer to take a step down in bench or low-end starter shooting guards in exchange for an improvement at another position. The abundance of low-end shooting guards means you are giving up the more easily replaceable commodity.

4. There are enough top-30 centers for most, but not all, teams to have one. Then there is a big drop. There are a bunch of centers available 50th to 125th overall, and then the position becomes a wasteland. If you can acquire two top-30 centers, then you should have a significant advantage at the position against most opponents. League settings and standings are always crucial to evaluating any trade, but generally speaking, I recommend pursuing two-for-two trade, in which you turn a top-30 point guard or power forward into a top-30 center, and in exchange give up your lower-ranked center for whatever position you gave up.

5. It is almost impossible to get fair value for James Harden or Giannis Antetokounmpo. They are too far ahead of the next best shooting guards. Even though Kevin Durant, a SF/PF, is first in the overall rankings, a trade of Harden or Antetokounmpo for Durant would usually result in lost value for the team getting Durant. The shooting guard spot in their lineup would fall precipitously, while the other team would likely replace Durant with a far more capable SF or PF. The only reasons worth trading Harden or Antetokounmpo are: you expect one to miss games; you expect their play to get significantly worse; or your roster needs significant adjustment, such as you severely lack depth and are acquiring multiple top-50 players, or you are in a roto league and need to make a major adjustment to focus on specific categories.